Dr Lee Campbell, artist, curator and Associate Lecturer on BA (Hons) Performance: Design & Practice at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London and Fine Art at University of Lincoln

Technoparticipation is a project that started in 2015, which aims to explore how ‘realia’ can be integrated into arts education. The word realia refers to objects from everyday life, used to improve students' understanding of real life situations, and ‘facilitate[s] the [creative] process’ (Piazzoli, 2017). This article explores applications as everyday digital realia – Skype, Textwall and TitanPad – to consider the benefits and drawbacks of using realia in the classroom. These tools facilitate a wider consideration of other digital applications that could be employed as digital realia in teaching and how, as Paige Abe and Nickolas A. Jordan suggest, ‘using social media in the classroom creates a new pattern of social encounter’ (2013, p.17).

communication skills; participation; peer assessment; realia; reflective practice; technology-enhanced learning

Everyday objects or ‘realia’ are used in teaching to improve students’ understanding of real life situations within the discourse of foreign language teaching (Budden, 2011; Harmer, 2007; Richards et al., 1992). As this article explores, they are equally applicable in arts education. For example: the well-known free communication application ‘Skype’, enables voice and video calls as well as instant messaging. Similarly, ‘Textwall’ is a free messaging app that allows students to post anonymous messages onto an online ‘wall’ (which are then sent to a group via SMS), where another free messaging app, ‘TitanPad’ allows students post messages (anonymously or otherwise) onto an online ‘wall’. Inspired by my experiences teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL), this article explores how these apps were deployed in an art school environment alongside wider literature and theories on their integration into art and design classrooms. Feedback from students who have used these apps (Skype, Textwall and TitanPad) in my classes took the form of spoken comments made in reflective discussions held after sessions making use of one or more of these apps. Student comments also took the form of written feedback using the apps Textwall and TitanPad – these apps proved effective means of gathering student feedback.

Art and design as disciplines require technical skills and abilities that mean art colleges in providing education, as well as training, emphasize ‘experiential learning’ as part of core teaching philosophy. As will be discussed over the course of this paper, digital (as opposed to object-based) realia were integrated into this fine art context. As part of a Loughborough University Teaching Innovation Award, I undertook a project that aimed to extend teaching as practice-as-research during the academic year 2015/2016 (Ingham, 2015). This involved developing learning strategies with a focus on technology-enhanced and blended learning, under the portmanteau/umbrella term ‘Technoparticipation’ (Figure 1).

Using collaborative co-learning processes, it aimed to reproduce real life scenarios by incorporating digital realia into the classroom in real life discussions/objects/situations that facilitate kinaesthetic learning experiences. As well as being a fine art tutor I have worked as an English as a foreign language teacher, where realia is often used to help learners get to grips with the target language. Everyday realia, often in the form of day-to-day conversational gambits and role-play situations are a means of provoking kinesthetic learning. Realia not only stimulate the mind, they encourage creativity by inviting students to engage different senses in multisensory learning environments.

Presenting real objects rather than representations echoes important moments in the history of contemporary art. As both method and object, the realia connects with the content and interests of fine art students. Avant-garde artistic practices of the early twentieth century, when artists made use of the ‘readymade’ and the ‘objet trouvé’ (found object). This historical pinpointing is important in informing Pop Art in the 1950s, and the subsequent development of theatre into art and the eventual emergence of Performance Art in the 1960s. This final creative form valorises actual presentation of the self (and one’s body) rather than a representation of the self.

When teaching fine art, particularly within a programme that emphasises student engagement with performative modes of practice, it is key that students are made aware of the possibilities for affective/sensorial encounters in varied artistic situations.

In expanding upon and unpacking the focused use of technology in the classroom this paper theorises how I have used different forms of digital realia including aspects of interruption as a phenomenological approach to performative teaching and learning.

When designing teaching activities, it is helpful to ensure that they do not displace students’ unique life experiences. On the one hand, teachers such as myself are keen to build students’ digital literacy by helping them to engage with multiple technologies. But on the other, I use the virtual classroom to prompt statements and responses from students as to these limits, using the learning environment as a space to not only reflect upon artistic practice but also to produce it.

Although the article explores positive application of technology in the classroom, it also acknowledges some of the difficulties, what Peter Williams refers to as the ‘threats [that] technology poses to teachers’ existing practices and the perceived maintenance of control’ (2008, p.213).

As a teacher, I have experienced and seen the emotional implications attached to ‘technological failure’ (Abe and Jordan, 2013, p.20). As part of Continuing Professional Development (CPD), I took part in a series of teaching observations, to enable me to reflect upon how my teaching practice could be developed. As part of this process, I was required to formatively observe a colleague. Then, shortly after, a summative observation of my practice was undertaken. As the lecture took place and I observed what happened, the lecturer was faced with a succession of technology problems mainly relating to poor internet connectivity. These resulted in the lecturer only being able to show only a couple of the YouTube clips they had intended. The lecturer was completely unprepared for technological disruption and I could see (and so could the students) that this had a negative emotional impact at the time. This situation embodies Nick Selwyn’s discussion of why some teachers are reluctant to use technology, as failure may result in compromising or destabilising ‘authority, status or control in the classroom (2011, p.101).

A key question during that arose during this observation was how best to proceed when it malfunctions. An issue that arose in a session that I taught, which was likewise observed by another participant in the programme, which explored what constitutes effective sketchbook practice. This was achieved through a collaborative intervention taking place between them and a (physically present) guest speaker (a third-year undergraduate Fine Art student) and a Skype call to a (physically distant) guest speaker (professional artist, Helen Cann). Fostering collegiality between myself, the students, one of their peers (the third-year student) and a professional (Helen), we all shared examples of our effective sketchbook practice. When Helen attempted to engage the students in a live drawing activity via Skype, the lack of a sound system impacted upon the activity. There was no built-in computer or data projector and no obvious sound system. This meant that some students found it difficult (and sometimes impossible) to hear.

In the observer’s analysis of my teaching session, I was commended for my use of technology (though hindered by the total lack of facilities in the room, which was not counted against me). To avoid any further awkwardness and embarrassment in front of my students, I now make sure to equip myself with not just having a plan B, but a plan C and so on. To that effect, I also verify that the materials presented to students via virtual means are available in physical forms. Since the technology (AV equipment) completely malfunctioned during my observed teaching session, I have made it a point to ensure that technicians visit the classrooms where I am teaching before I conduct lessons, as they are heavily reliant on technology.

Inspired by previous experiences using Skype in the EFL classroom – where it was used to conduct tutorials with students from all over the world – the Technoparticipation project was not a ‘how to use Skype’ or a shortcut instruction manual session, but rather it explored, identified and implemented Skype to:

By exploring Skype as a means of exploring as well as of creating ‘performative embodiment’, follows on from what Ray Land, Julie Rattray and Peter Vivian refer to as liminality, a ‘transformation state [that] entails a reformulation of the learner’s meaning frame and an accompanying shift in the learner’s ontology or subjectivity’ (2014, p.5). Such a space/state renders the human body as ‘transgressive’, neither wholly present nor entirely absent when restricted to online presence.

Skype enabled me to achieve two key aims: 1) build students’ effective e-communication skills, and 2) provoke opportunities for students to learn about some of the practical realities of being a professional artist first-hand. Fulfilling these aims, the project invited artists to speak to students virtually via Skype during lectures and seminars, bringing students into direct communication with established experts in their subject. As part of teaching sessions for the BA in Performance: Design and Practice (P: D&P) at CSM, Skype was implemented into seminars in contextual studies.

Students had the opportunity to ask direct questions relating to her experience of the seminar topic, which explored the role of documentation in performance (Figure 2).

At the end of the session, reflective discussion enabled students to evaluate their learning, which provided insights as to the effectiveness of encountering a virtual guest speaker in this way. Student behaviour throughout the session indicated that I had achieved my aims. Many students enjoyed gaining knowledge directly from the speaker via Skype, rather than through secondary sources. This echoes teacher Megan Poore’s suggestion that Skype ‘promote[s] free-flowing, real-time conversation, which can support peer learning, brainstorming and creativity’ (2013, p.122).

Further to these in-class applications, a separate ‘performative lecture’ was held as part of the overall Summer Lodge in 2015, an annual initiative that brings together a diverse group of artists with staff members from Nottingham Trent University, with the aim of fostering experimentation (NTU, 2015), as a way of disseminating aspects of Technoparticipation.

Previously in this paper, I have suggested that realia not only stimulate the mind, they encourage creativity by inviting students to engage different senses in varying encounters. However, what happens in terms of embodiment and the senses when realia take virtual forms?

During the course of the lecture, invited speaker/participant, Dani Abulhawa, described her experience as a Skype speaker in the programme at CSM and reflected on the difference between virtual as opposed to (physical) face-to-face communication (Figure 3).

Whilst speaking she did not know how or whether the student audience read or registered what she said, which was unsettling, as she could not read what was going on in the room. Her dialogue suggested that audience feedback in terms of bodily nuance – frowns, smiles, or nodding for example – were important in creating this. As Abulhawa indicates, there are complex issues surrounding the possibilities for digital realia to provide affect (Abulhawa, 2015).

In workshops delivered at the University of Lincoln and Central Saint Martins (UAL) a key strategy has been to use staged interruption as a form of realia (Campbell, 2017). When reviewing this strategy of performative pedagogy, Aengus Kirakowski suggests that staged interruptions ‘blur the difference between performance and reality – coaxing the student into a “real” scenario where they will have to interact in the language’ (Kirakowski, 2016). Referring to my specific usage of staged interruption, he suggests that what is interesting is that this methodology was ‘inspired by the use of technology, which created a kind of detachment in the participants, allowing them to more easily shed their student-roles and enter a liminal state in which they will more willingly and opportunistically use what they have learnt so far’ (ibid.).

Students were (mostly) in favour of Dani Abulhawa presenting via Skype-in, but one student bemoaned the sudden ‘breaks’ in Abulhawa’s virtual presence due to the patchy internet connection, which caused visual freezing and sonic fragmentation. Another student suggested that these sudden breaks in connectivity prompted her to consider how social communication may be viewed as a fragmented exchange – that the ‘breaks’ that are inherent to Skype are extreme versions of communicative fragmentation. Taking this further, I then designed a teaching seminar for the same group of students on (virtual) interruption as realia. Peter Bond suggests that real life reproduction needs to incorporate aspects of interruption (2016).

The class then discussed deliberation, contestation and debate about how creative practitioners have successfully deployed interruption as an artistic strategy. To extend discipline-specific and generic literature and fuel awareness of a contextual framework, they were alerted to the work of duo Morrad+McArthur (Annie Morrad and Ian McArthur) who use the reverb echo of Skype. Where most try to engineer the reverb out (as it interrupts the free-flow of social exchange in a two-way conversation), the duo exploit this ‘glitch’. This connects with their artistic practice, generating sound disruption via improvisation to create complex layered recordings (Morrad, 2015).

Accordingly, to exploit Skype’s potential for interruption and to enable students to gain knowledge of interruption in practice students undertook conversations with virtual speakers (via Skype), who discussed practices of generating artistic ‘interruptions’. At moments, students were unsure whether the visual freezing and sonic disruption that occurred were pre-engineered or not, blurring zones of demarcation as to whether the interruptions were ‘art’ or ‘life’. Uncertainty was further heightened when half way through the seminar, a fire alarm sounded – this was an actual fire alarm. Many of the students were convinced that the alarm was phoney.

During a subsequent iteration of the Technoparticipation lecture at NTU, at University College Cork (UCC) that same year, speaker Dr Mark Childs referred to the effects of virtuality, onlineness and dislocating the body, suggesting that the body is problematized by virtual spaces (Childs, 2015). Heckling is predicated upon interruption, using both body and language (Campbell, 2016). In relation to Childs’ ideas, does the heckler then lose his body as a tool to interrupt and resign to use (only) verbal language when engaged in virtual space? Does virtual space negate his body’s potency? With these and Abulhawa’s insights into the potential difference between virtual and physical in mind, an undergraduate Fine Art teaching session was designed and delivered to first year students at the University of Lincoln, part of the module ‘The Fine Art Body’. During the session, students were invited to take part in an activity entitled ‘Speak with your mouth full’. They experienced heckling and interruption briefly in the physical world before exploring what it means to heckle and interrupt in the virtual. They underwent a series of activities exploring the effects that virtuality and onlineness may have on the body in terms of social communication and the power to interrupt through a series of performative constructs. Like hecklers, the students used their body – its corporeality – to assert opinion. This activity reappraised students’ attitudes towards themselves operating as actors within any discussion space where they are physically there and not: in the real physical world you are known, you can’t just hide like an internet ‘troll’ (an online version of a heckler). In a reading group, students participated in a series of body-related activities that may be considered as incongruous and unacceptable when undertaking ‘serious’ debate. For example, speaking with your mouth full, brushing your teeth, standing on your head, doing the conga, attempting a limbo and so on, the students reflected upon the importance of the body as a means of communicating individual opinion in everyday social communication.

Technoparticipation has since been developed into a first-year Academic Support workshop entitled ‘On Reflection and Critical Thinking’ for students on the BA in P: D&P at CSM. Extending usage of Skype, the workshop deployed the digital apps Textwall and TitanPad as tools that facilitate a blended learning environment. Feedback from students evidences how these technologies provided useful platforms for students to engage in live contestation, deliberation and debate with their peers through live forms of writing and rumination about provocative forms of Performance Art. Learning outcomes included: enabling students to understand and describe key concepts relating to critical thinking and reflective practice; discuss effective communication skills using e-technology; and develop effective argumentative skills.

The workshop On Reflection and Critical Thinking, supported learning by evidencing how students utilised reflective practice as a skill demonstrating how self-reflection as an artist can be embedded into teaching and learning. As Jack Mezirow discusses, such reflective approaches to practice need to be taught, because they allow transformative learning (1991). They galvanise critical thinking, by identifying critical incidents that have helped shape students’ thinking and help them address the implications of their practice, thus facilitating them to act upon those realisations in the future.

Introducing students to a reflective model enabled teacher and students to find common ground as practitioners. This approach involves stages – Anticipation, Action and Analysis – developed as part of PhD research (Campbell, 2016). This method involves ‘present[ing] an original, practical and imaginative way of demonstrating reflective practice’ (Newbold, 2016). The model builds upon another by Gary Rolfe, which uses key questions in its stages – What? So What? Now What? (Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper, 2001). The adapted model involves three stages:

At the start of the session, the ‘Anticipation’ process is explained and students are given contextual reference points to facilitate reflective practice (Rolfe, Freshwater and Jasper, 2001; Savin-Baden, 2007). Another useful topic drew from Continuing Professional Development (CPD) workshops on reflective practice that I had recently attended. Students were alerted to discussions taking place between participants as a form of realia. Students then tried the model with a view to later increasing their autonomy by developing their own versions.

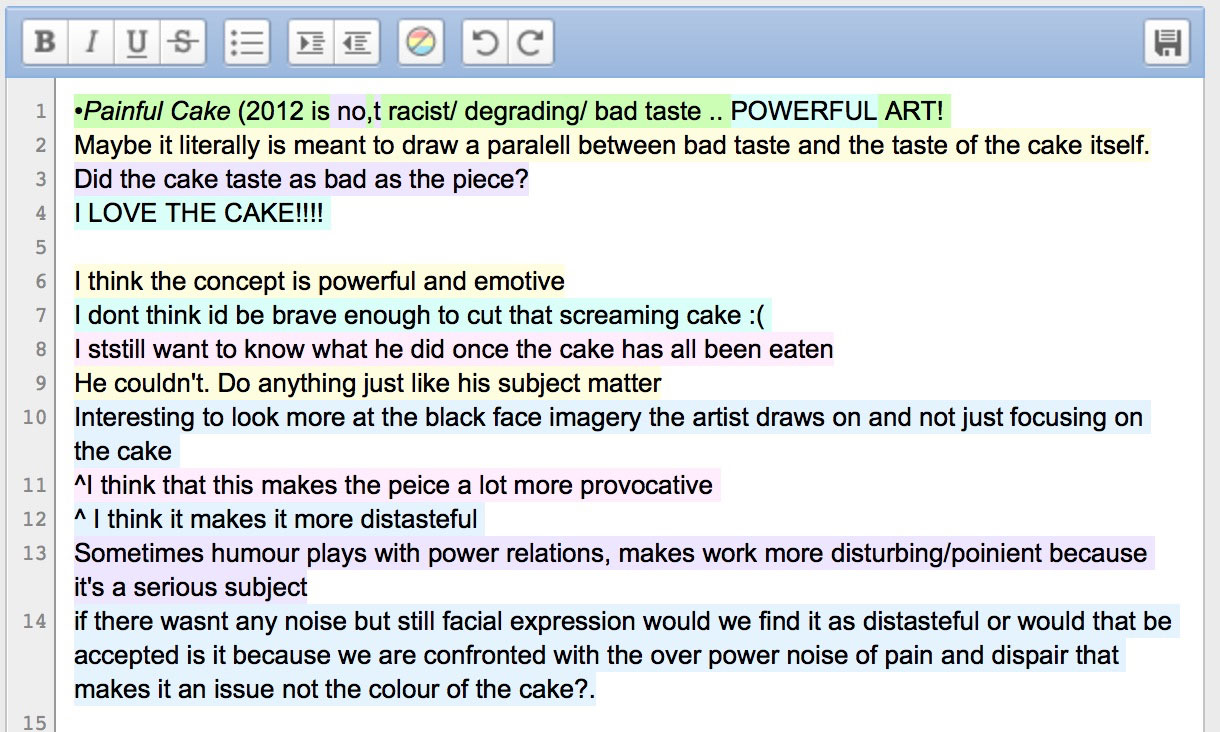

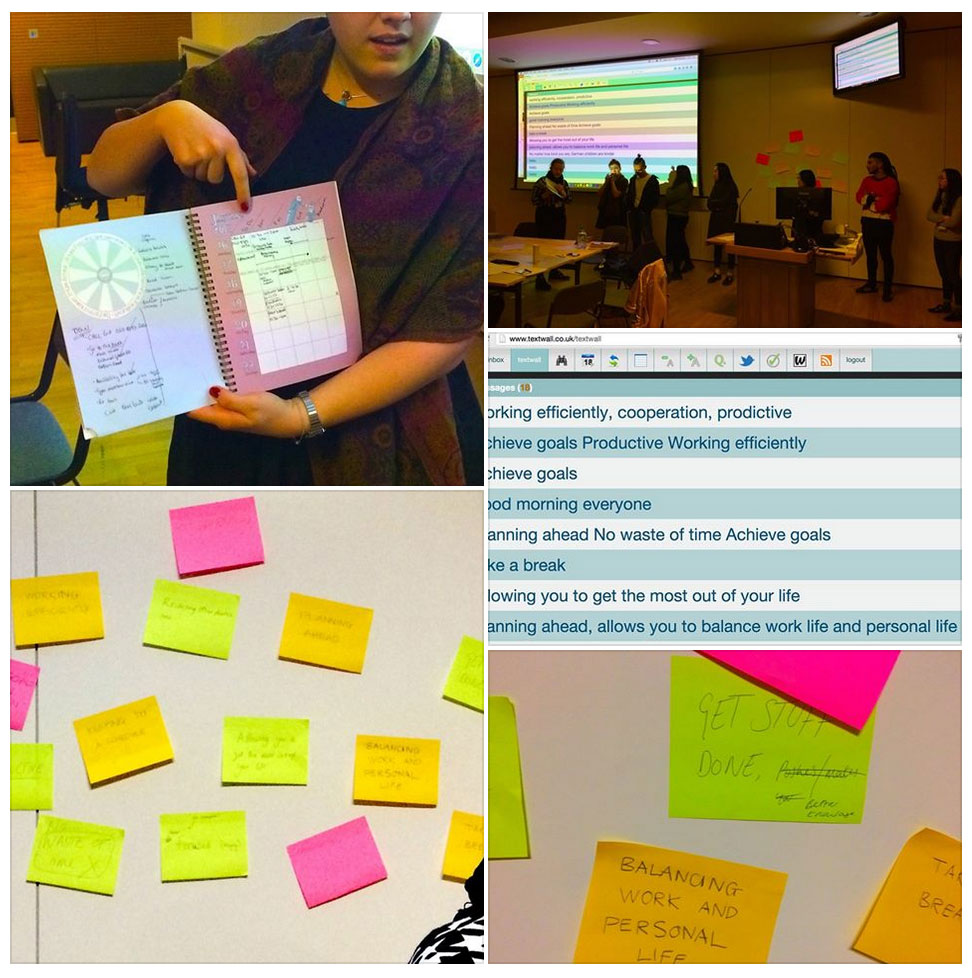

Students viewed a video clip documenting the performance Painful Cake by Swedish artist Makode Linde at Moderna Muséet, Stockholm (May 2012). The video depicts a torso made of cake lying on a white table, instead of a cake face however is Linde’s own face, both of which are painted, seamlessly designed to depict a caricature of an African woman. As part of this performance, visitors are invited to cut into the cake – while Linde screams in pain. Despite initial humorous reactions, it was intended to raise awareness of female genital mutilation, recalling the violent nature of imperial colonisation of Africa and the damage it inflicted on the people there. King Leopold of Belgium famously referred to European nations claiming slices of the ‘African cake’. As students watched the clip, they were asked to reflect upon this provocative piece and write ideas on post-it notes to help put them into concrete terms, which were then displayed on the wall and moved around (Figure 4).

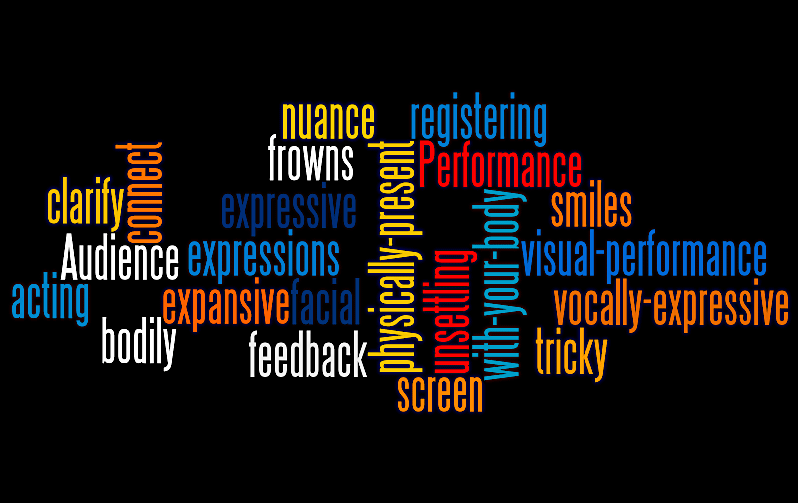

In this way, the learning process started by using 'analogue' realia – post-its/pen and paper – which were then translated digitally, as students converted what they had written into an image via Wordle.net. Wordlle.net is an application that enables text to be imported and visually arranged into a word-cloud.

When importing a large block of text to be converted into a word-cloud, the frequency that a particular word appears in the block is considered and given visual prominence, those (higher frequency) words appearing larger in size than other (less frequency) words. Having this visual hierarchy of words configured for them, students have told me that this can be extremely useful when working out how they place focus on certain words as keywords and key concepts, particularly in terms of when they are faced with doing writing exercises that demand that they be focused in terms of key concepts e.g. the final year written dissertation.

In converting the images students are encouraged to use mobile phone technology – another important realia. Mobile phone technology is part of most people’s everyday culture; many students use their phones all the time. Ron Berk goes so far as to suggest that this form of technology operates as ‘appendages to [students] bodies’ (2009, pp.3-4). By and large students know how to fully operate their mobile phone and this means that there is nothing technical for students then get to grips with when participating in the activity. Abe and Jordan ask whether ‘educators have [time] to teach students how to use social media’ (2013, p.20). Following on from this, Sarah Eaton (2010) focuses heavily on the fact that Skype’s easy-to-use technology makes it attractive for teachers aiming to integrate social media into their teaching. Reasons for using mobile phone technology echoed those for using Skype: they are both familiar to me (and the students) and do not require either party to be particularly tech-savvy.

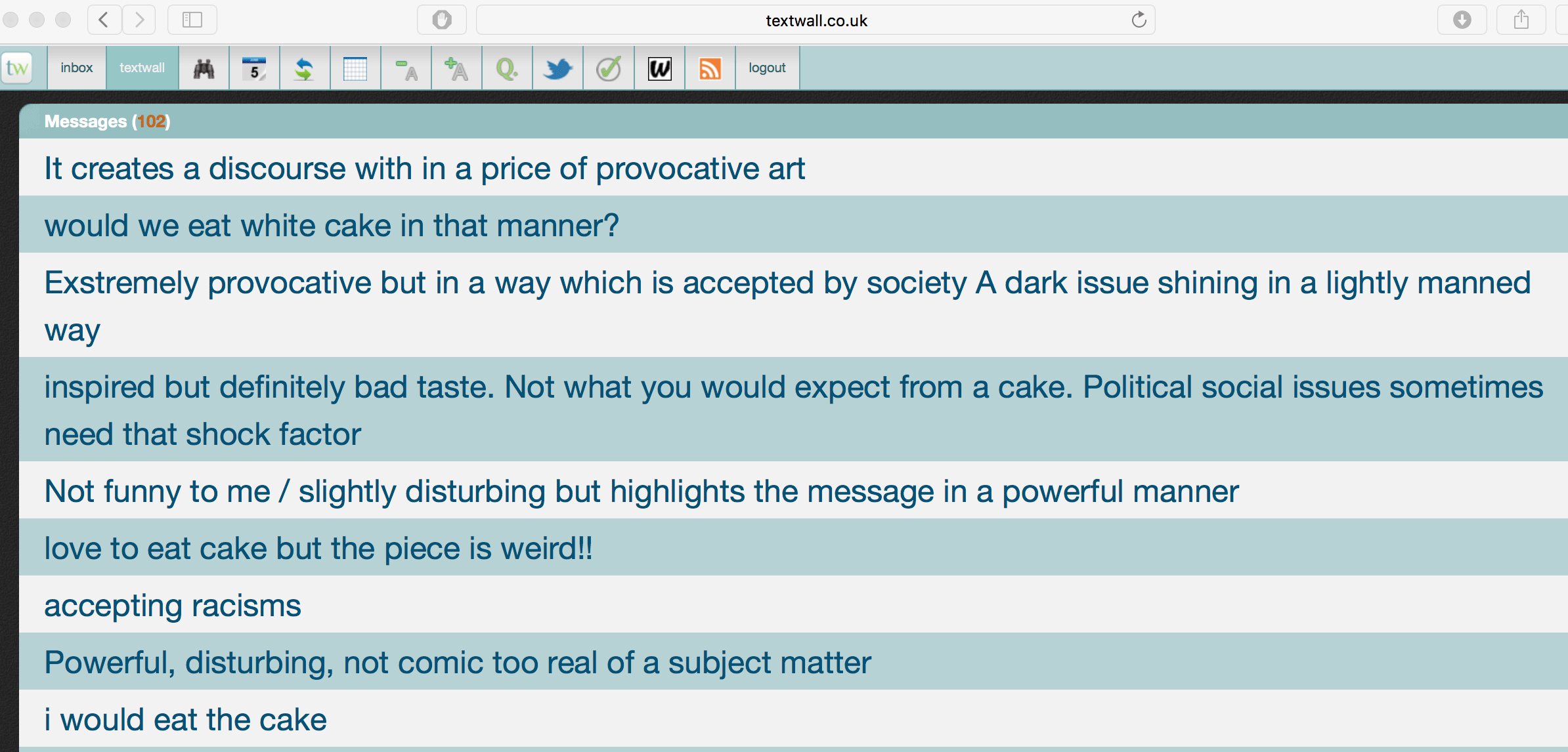

The Textwall activity started by me posting the statement ‘Painful Cake is racist/degrading/bad taste ... BAD PERFORMANCE ART’ – inviting students to respond with anonymous comments. The activity provoked healthy debate amongst students about what constitutes (un)acceptable behaviour in performance. Similarly, when trialled as part of a different first year undergraduate Fine Art seminar at the University of Lincoln a month prior, students engaged in public discussion (responses listed in Figure 6 below).

Debate related to the intersection between humour, comedy and participative and performative modes of art practice. A subsequent lecture to the same students and the whole year group, then referred to the anonymised Textwall comments to initiate wider discussion of issues relating to art and cultural appropriation.

Maggi Savin-Baden’s theories on the interplay between ‘reflection’ and ‘interruption’, consider moments of reflection as interruption as catalysts that provoke self-reflection and deep critical thinking (2007). This provocation informed the second stage of the practice model – ‘Action’. Her ideas were discussed by the class and informed a learning activity where students produced flash-mob style performance art interruptions around Kings Cross railway station in London (a short walk from CSM).

However, reflection was not viewed, in respect to Savin-Baden’s ideas, as being a form of interruption, but rather how interruption (and its alliance with the unexpected and surprise) can force immediate critical reflection and a call for spontaneous decision-making and action. Interruption can advance learning; the interruptions were intended to provoke audience awareness (and potential reflection) of a socio-political/environmental/personal issue chosen by the student groups.

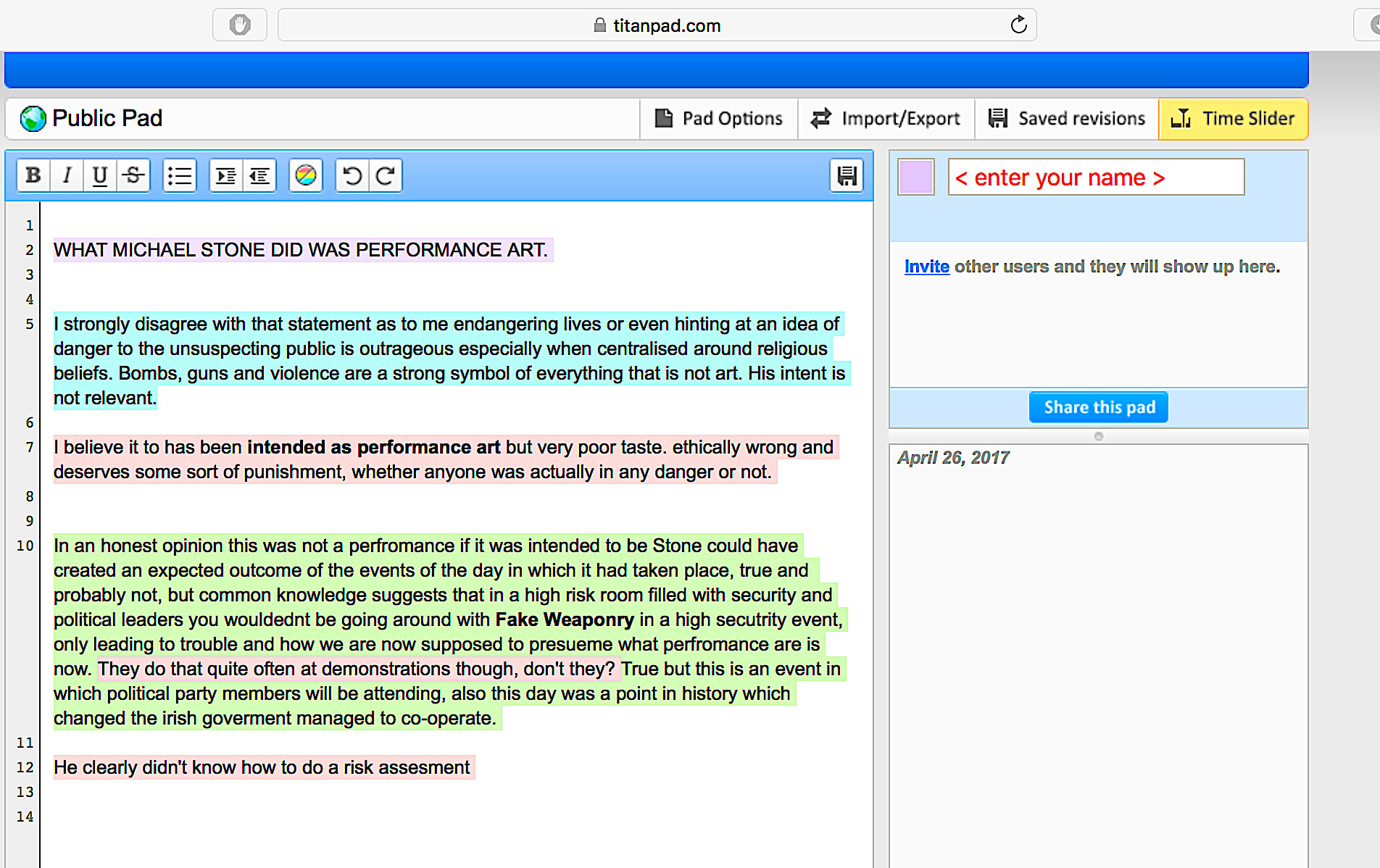

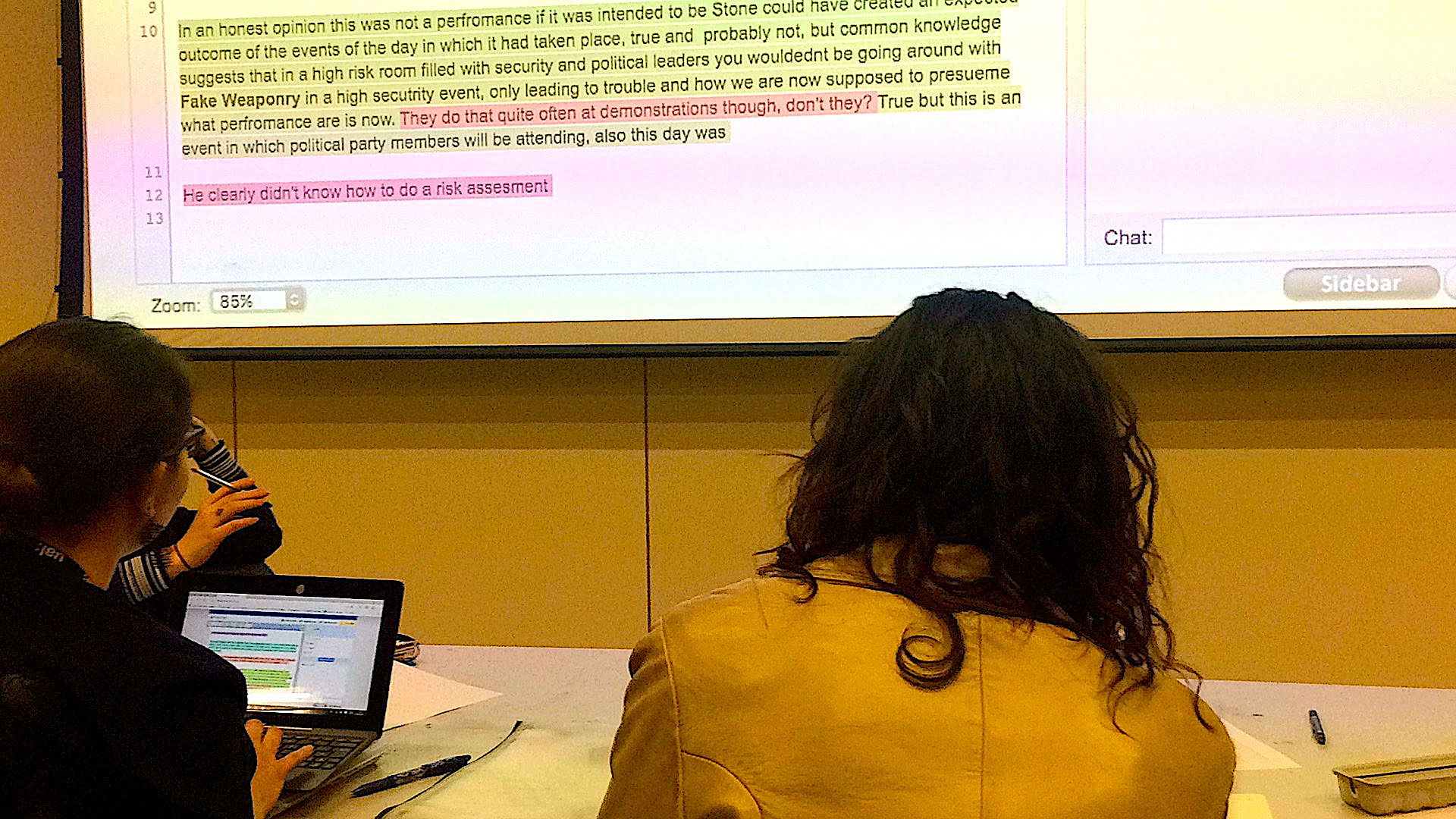

The third ‘Analysis’ stage encouraged students to reflect upon their flash-mob interruptions as provocative demonstrations of performance art. This exercise again referred to another example, in Michael Stone, who, in a court of law, claimed that an act of terrorism was a piece of performance art. Encouraging students to debate what constitutes Performance Art as a discipline, students were asked to read a handout outlining the Michael Stone legal case and apply their own criteria. To trigger student’s critical thinking, they were asked to respond to the following statement: ‘What Michael Stone did was Performance Art’. Some students used their mobile phones whilst others typed on laptops (pictured in Figures 7 and 8 below).

These responses were projected onto a wall in the classroom, so students could see one another’s responses as they were typed, a more immediate form of live messaging. TitanPad is used in professional practice to overcome the difficulties of physically meeting. When co-authoring or co-writing documents, Google Docs also enables collaborative document sharing/editing online, allowing authors to see where different people make changes. The visual appearance of these revisions (being able to see the revision history visibly) recalls Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), in which he erases an artwork by Willem de Kooning, but traces of the lost de Kooning artwork are still evident, just under the surface. There is little/no pedagogic literature suggesting that Google Docs (and TitanPad respectively) could be made public via projection in a classroom setting, enabling potential live writing activities, where everyone can witness writing as a live collaborative process. Poore suggests that as a platform Google Docs underlines to students that ‘writing is an ongoing process of revision and refinement’ (Poore, 2013, p.136).

Extending these ideas, TitanPad (as an app which offers features similar to Google Docs) was projected onto the wall in class, so that everyone could engage in a live collaborative writing activity (Figures 7 and 8). David J. Nicol and Debra Macfarlane-Dick outline the importance of peer assessment and feedback (2006). Using TitanPad in class in this way (during the ‘Analysis’ stage), provided students with a live form of peer feedback – sharing ideas, (dis)agreeing with others and galvanising quick opinion formation.

After a 30 minute TitanPad writing session in which students debated the Stone case, they revisited Textwall posts on Painful Cake. This initiated further discussion, reflection, made further use of TitanPad facilities and allowed them to extend their ideas by taking advantage of the greater word-count options, as they chose how and if they would interject/revise/correct/contest the ideas of their peers. Again, this elicited much classroom debate (Figure 9).

Reflective discussions via email conversations with students helped me evaluate the effectiveness of the teaching activities at each stage, and consider how technology supports an inclusive learning environment, accessible to all. During post-session reflection sessions in the first Skype stage of the project, one student commented that the interactive elements of this app were a great way to illustrate the ideas discussed in-class, namely the role and forms of interruption, as well as offering a platform to interact with different professionals working within the industry. From feedback in later sessions using different realia, it is clear that most of the students consider Textwall to be an effective means of encouraging those who do not wish to be identified, are too nervous to ask a question or share an idea to participate in group discussion.

Suggestions that students could also use online social media, namely Twitter, in the same manner were met with opposition in feedback sessions, reflecting Rena M. Palloff and Keith Pratt’s observations of student ‘resistance’ to such means, partly due to issues of privacy and anonymity (2013, p.34). Some students also observed that Twitter has a character limit and can be restrictive. Yet it could be argued that giving students this restriction forces them to use more concise language. As students acknowledged, Textwall has no maximum word-limit per-post, but lengthy posts would involve a lot of typing on mobile phones and might cause physical discomfort. Students told me that during the TitanPad activity, they enjoyed being able to write a lot, see who had written what – ‘knowing exactly who is part of the conversation’ (student feedback comments, Campbell, 2017) – and edit other people’s comments (unlike Textwall). As one student observed, TitanPad is a ‘great tool to re-assess our opinions and record how the debate unfolded’ (student feedback comments, Campbell, 2017). It was ‘useful for having instant interactions in which you can interject one another’s comments and thoughts without creating arguments and speaking over one another. All voices can be heard’ (student feedback comments, Campbell, 2017). Another student suggested that Textwall’s anonymity ‘allows total freedom of speech’ (student feedback comments, Campbell, 2017). TitanPad offered students a means for them to share their ideas online and enable them to identify themselves as the author and edit/contest the ideas of their peers, possibly causing discomfort for some. Although, some students enjoyed the anonymity of the Textwall activity, they were curious to find out who had written what and some wanted to identify themselves as the author. This connects with Abe and Jordan’s technique of establishing a Twitter hashtag that enables students to both view and identify responses (2013, p.17). An ideal digital tool would enable students to identify themselves but also make it possible for other students to contribute anonymously should they prefer.

As a model, the Anticipation, Action and Analysis process employed in the final workshop, enables a diverse range of students to engage in deep learning. One of the students has since adopted it to his way of working, which has helped create flow between theory and practice, something which he had struggled with previously. Other students commented that they found this process useful as it enables them to evaluate different interpretations and different approaches to generating practice. For example, one student has developed a process of reflection by using colour coding and written notes (which were used in the workshops) as a simple but useful means to structure and enhance his reflective writing.

Poore questions whether it is possible to identify students with special needs ‘as regards to their digital participation’ (2013, p.184). Comments from students with dyslexia suggested that they felt pressurised keeping up with the live writing process attached to my use of TitanPad in terms of the time it would take them to generate written responses to other students’ posts. Their feedback aligns with Poore’s follow-up question, about the ways dyslexic students are often precluded ‘in their ability to participate in social and cultural life online’ (2013, p.184). Some students may feel uncomfortable about being ‘noticed’, preferring the anonymity that Textwall allows, whilst others take advantage of being able to reveal their identity and try to make themselves appear the centre of attention.

With this feedback in mind, and meeting the needs of all learners vital to ensuring a supportive collaborative environment, initial guidance for technology-related activities, issued at the start of each session, is key in ensuring that the use of digital realia facilitate student learning. When using TitanPad or a similar app like Google Docs in the classroom, it is important to ensure that clear expectations are set out to students to enable them to focus on a given task in a manner which advances the learning of all and helps alleviate anxieties, particularly for students with learning difficulties such as dyslexia. Furthermore, by setting clear supportive guidelines it is possible to emphasise the inclusivity so important to collaboration. During these workshops students were told that the TitanPad document should be viewed as a group effort, as a collaborative document.

This article has drawn upon examples of teaching practice during the Technoparticipation project that integrated different forms of realia, namely Skype, Textwall and TitanPad. As part of the project, other realia were employed in conjunction with these apps, in exploring how we can foster social interaction and debate. Although the emphasis has been on the digital in the Technoparticipation project, tangible realia are nevertheless important, for example post-it notes transitioned into virtual realia – and other translation tools included mobile phones and Wordle.net. For instance, as part of an Academic Support workshop I gave at CSM on the BA P: DP in March 2017 on the topic of time management, one student discusses how she makes use of her diary to effectively time-plan (Figure 10).

Abe and Jordan ask how virtual realia may potentially create ‘a new pattern of social encounter’ (2013, p.17). In response, I suggest that virtual realia and student engagement with such technologies can be construed as a form of student empowerment.

Student feedback is of prime importance evidencing how varying levels of author anonymity can be exercised and how ideas can be subjected to instant peer scrutiny when using virtual realia. The positive effects of technology in the classroom are tempered by the difficulties/challenges teachers can face in implementing them.

As the workshops integrated models developed during my own practice it could be said that teaching is an extension of this. In this way, such practice should be viewed less as ‘social encounters’ (Abe and Jordan, 2013, p.17) and more as ‘performative events’ (Nunes, 2006, p.130-131). Within this event the student is ‘anything but marginal’ (Nunes, 2006, p.130) and with the increasing importance of digital and virtual realities as a major component of students’ lives, never has there been a time in which the meanings of access are so broadened, via technological mediation. Despite this, it is pertinent to discuss and reflect upon issues of inclusion. For example, TitanPad offered students a means of sharing ideas online; but identifying themselves as the author and editing or contesting the ideas of their peers, as indicated by feedback, was a cause of discomfort for some students.

Key findings of these teaching experiences relate to the inclusiveness, inherent to the nature of Textwall and TitanPad as applications. This is backed up by comments from different students, which help explore the ways students ‘participate in social and cultural life online’ (2013, p.184).

Using these findings, I will connect these to the next stage of the project: developing guidelines for the running of digital realia workshops and use feedback included throughout this paper to influence the design of these workshop models.

These models will underline the importance of teachers giving students initial guidance for technology-related activities issued at the start of each session as key in ensuring that technology supports student learning as a collaborative experience. It is the role of the teacher to create and maintain a safe space for all students, supporting and enabling them to actively engage in the experimental risk-taking vital to fine art (and arts) education.

Abe, P. and Jordan, A.N. (2013) ‘Integrating social media into the classroom curriculum’, About Campus, 18(1), pp.16–20. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/wol1/doi/10.1002/abc.21107/abstract (Accessed: 28 June 2017).

Abulhawa, D. (2015) ‘Technoparticipation lecture’, Summer Lodge, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, 12 June.

Berk, R. (2009) ‘Teaching strategies for the net generation’, Transformative Dialogues: Teaching and Learning Journal, 3(2). Available at: http://www.kpu.ca/td/past-issues/3-2 (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Bond, P. (2016) ‘Roundtable discussion’, Tactics of interruption, Toynbee Studios, London, 9 June.

Budden, J. (2011) ‘Realia’, Teaching English (British Council, BBC). 6 April. Available at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/realia-0 (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Campbell, L. (forthcoming 2017) ‘Collaborators and hecklers: performative pedagogy and interruptive processes’, Scenario: Journal for Performative Teaching, Learning, and Research, 9(1).

Campbell, L. (2016) Tactics of interruption: provoking participation in performance art. Loughborough: Loughborough University.

Childs, M. (2015) ‘Technoparticipation lecture’, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland. 3 September. Available at: https://performancepoliticsprotest2015.wordpress.com/pre-symposium-event-technoparticipation/ (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Eaton, S. (2010) ‘Using Skype in the second and foreign language classroom’, Social Media Workshop, Get your ACT (FL) together online: standards based language instruction via social media, San Diego, CA, 4 August. Available at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED511316 (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Harmer, J. (2007) The practice of English language teaching. 4th rev. edn. Harlow: Pearson Longman.

Ingham, D. (2015) ‘#technoparticipation – practice-as-research’, Teaching and Learning Blog, 15 July. Available at: http://blog.lboro.ac.uk/teaching-learning/2015/07/27/technoparticipation-practice-as-research/ (Accessed: 6 July 2017).

Kirakowski, A. (2016) ‘We interrupt this broadcast…’, Createtechnica: Music, Creativity and Technology, 15 May. Available at: http://aengusk.com/education/we-interrupt-this-broadcast/ (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Land, R., Rattray, J. and Vivian, P. (2014) 'Learning in the liminal space: a semiotic approach to threshold concepts', Higher Education, 67(2), pp.199–217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9705-x.

Linde, M. (2012) Painful Cake. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/user/klubbficks (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Mezirow, J. (1991) Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Morrad, A. (2015) ‘Technoparticipation lecture’, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland. 3 September. Available at: https://performancepoliticsprotest2015.wordpress.com/pre-symposium-event-technoparticipation/ (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Newbold, C. (2016) Email to Lee Campbell, 15 January.

Nicol, J.D. and Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006) ‘Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice’, Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), pp.199–218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03075070600572090.

Nottingham Trent University (2015) ‘Lee Campbell (30.06.2015)’, Summer Lodge. Available at: http://www.summerlodge.org/portfolio/lee-campbell/ (Accessed: 1 July 2017).

Nunes, M. (2006) Cyberspaces of everyday life. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Palloff, R.M. and Pratt, K. (2013) Lessons from the virtual classroom: the realities of online teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Piazzoli, E. (2017) Email to Lee Campbell, 20 June.

Poore, M. (2013) Using social media in the classroom: a best practice guide. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Richards, J.C., Platt, J. and Platt, H. (1992) Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. London: Longman.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D. and Jasper, M. (2001) Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Savin-Baden, M. (2007) Learning spaces: creating opportunities for knowledge creation in academic life. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Selwyn, N. (2011) Education and technology: key issues and debates. London: Continuum.

Williams, P. (2008) ‘Leading schools in the digital age: a clash of cultures’, School Leadership and Management, 28(3), pp.213–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13632430802145779.

Dr Lee Campbell is an artist, curator and lecturer in Fine Art at University of Lincoln and an Associate Lecturer on BA (Hons) Performance: Design & Practice at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. His practice explores how meaning is constructed through politics of space and the politics of artist articulated through visual and verbal languages. He has published extensively in journals/books including Performativity in the Gallery and PARtake: The Journal of Performance as Research. He is co-organising (with Lisa Gaughan) a conference entitled Provocative Pedagogies: Performative Teaching and Learning at University of Lincoln in October 2017.